Preamble What happens when we combine Swift’s conditional conformance with codability?

Swift 4 introduced the Codable set of protocols and made working with JSON a breeze, eliminating the need for a lot of boilerplate we previously had to write! Swift 4.1’s conditional conformance unlocks even more potential, and lets us delete even more boilerplate. Let’s take a look at one particular example.

Many APIs let clients fetch more data in fewer requests by providing a way to include related resources. For example, the Stripe API supports “expanding objects”: wherever the API may by default return a customer ID, the client may instead request a fully expanded customer data type.

In Swift, we can represent the idea of such an expandable object using the following type:

enum Expandable<Object: Decodable> {

case id(String)

case expanded(Object)

}

And we can conform this type to Decodable, capturing the ability to decode either an id or an expanded value depending on the payload:

extension Expandable: Decodable {

init(decoder: Decoder) throws {

do {

self = .id(try String(decoder: decoder))

} catch {

self = .expanded(try Object(decoder: decoder))

}

}

}

With this conformance, we can define a variety of decodable types with expandable properties.

struct Customer: Decodable {

let id: String

let email: String

}

struct Invoice {

let id: String

let customer: Expandable<Customer>

}

We now have a data type that will decode just fine, regardless of whether or not its customer property is fully expanded or merely an id, and it feels very reusable: any expandable property can use this Expandable type. Unfortunately, it’s still way more restrictive than it needs to be.

Our Expandable type is a specialization of another type that’s typically called Either and it’s typically defined in the following way:

enum Either<Left, Right> {

case left(Left)

case right(Right)

}

Either is the most generic, non-trivial enum that we can define: it has two cases with two generic, associated values. Expandable is an enum that wasn’t far off from this definition, and indeed we could have used Either to define Expandable using a type alias:

typealias Expandable<Object>

= Either<String, Object> where Object: Decodable

Either doesn’t conform to Decodable, though, so we’ve lost the ability to use this definition of Expandable in our earlier, decodable types. We can recover this loss, though, by using conditional conformance! Either can conform to Decodable as long as its associated types are decodable.

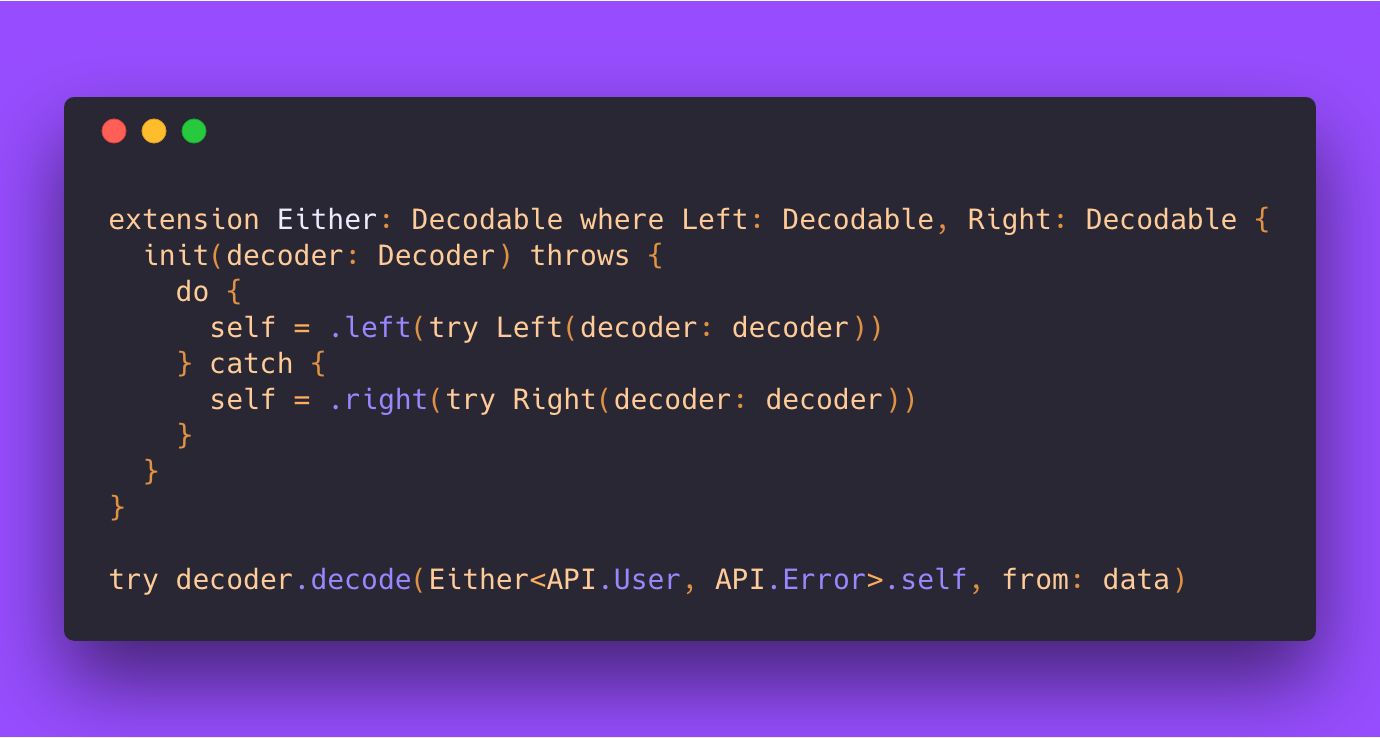

extension Either: Decodable where Left: Decodable, Right: Decodable {

init(decoder: Decoder) throws {

do {

self = .left(try Left(decoder: decoder))

} catch {

self = .right(try Right(decoder: decoder))

}

}

}

This short protocol extension fully generalizes the idea of decoding different kinds of values!

But what’s this kind of decoding good for other than expandable properties? Well, any time we expect to decode either one type or another, we can use Either. For instance, we can decode API errors alongside the API data types we hope to fetch. Given a struct that represents an API error:

struct StripeError: Decodable {

let message: String

}

We can now conditionally decode an expected data type or an error!

try decoder.decode(

Either<Invoice, StripeError>.self,

from: data

)

We were able to reuse our generalized solution for Expandable with a totally different use case. We didn’t have to write any more custom decoding logic: Either works like an if—else statement for decoding!

That’s two examples. How about two more for good luck?

APIs are long-living entities that develop quirks over time. Some endpoints may return a property as an integer, while others may return that same integer as a string. Our client can remain resilient and type-safe over time using Either, which lets us succinctly capture these two cases!

struct User: Decodable {

let id: Either<Int, String>

}

Let’s wrap up with one more example! It’s very common to save app state to disk and load it on app launch. Sometimes, this format changes over time, and older client data needs to migrate to a new format. If this data is decoded using Decodable, we can capture some of this conditional logic automatically!

let appData = try decoder.decode(Either<AppData, LegacyAppData>.self, from: data)

switch appData {

case let .left(appData):

// handle app data

case let .right(legacyAppData):

// migrate legacy app data

}

Conditional conformance gives us the ability to eliminate a lot of decoding boilerplate in a completely general, reusable way. If you want to look at some real-world code, we use this technique in our Point-Free Stripe client!